The Japan we fail to see, part two

Francesco Baldessari

Many of those who have been in Japan, even for decades, have never heard of ancestor's worship, or, if they have, like me until recently do not have a clear idea of what it is.

It is therefore a sobering thought that the Japanese spend more time on ancestors worship than on all other rituals put together.

¥270 billion are spent every year on the altars used to the purpose.

Chances are good that most of the Japanese you know practice it in a form or another.

Nor is it just a quaint tradition. Ancestors worship reshapes societies that practice it in ways that are profound and full of consequences. It is common to all the cultures of what we call the far east, but in Japan it has acquired special, extremely unusual characteristics that have contributed to making Japan what it is. It is the direct cause of much of the grief Japan has known in its history.

I am no expert on the subject, to the contrary, I just discovered the topic, but it has literally reshaped my understanding of Japan, an understanding (and hopefully not a ) that I want to share. The concept has also political implications (and in fact it concerns directly the Imperial House and its role) and I think we all should understand it.

I will cover ancestor's worship in a few posts. Those who are interested in Japan are invited to pay attention. I hope it will open their eyes as it opened mine. If they live in Japan, understanding ancestors worship will help them understand those they love.

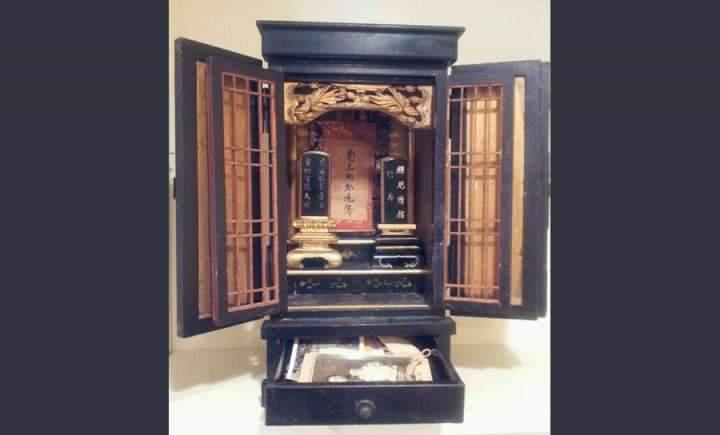

The following photo shows a butsudan, the altar the Japanese use to meet their dead.

They tell them the latest gossip, show them things, ask for advice. The Japanese do not accept and positively refuse The idea that the death of the body means the end of a relationship.

In fact, I think it is better to say that to the Japanese the dead are still alive and the same they were before. They just no longer have a body.

Francesco Baldessari