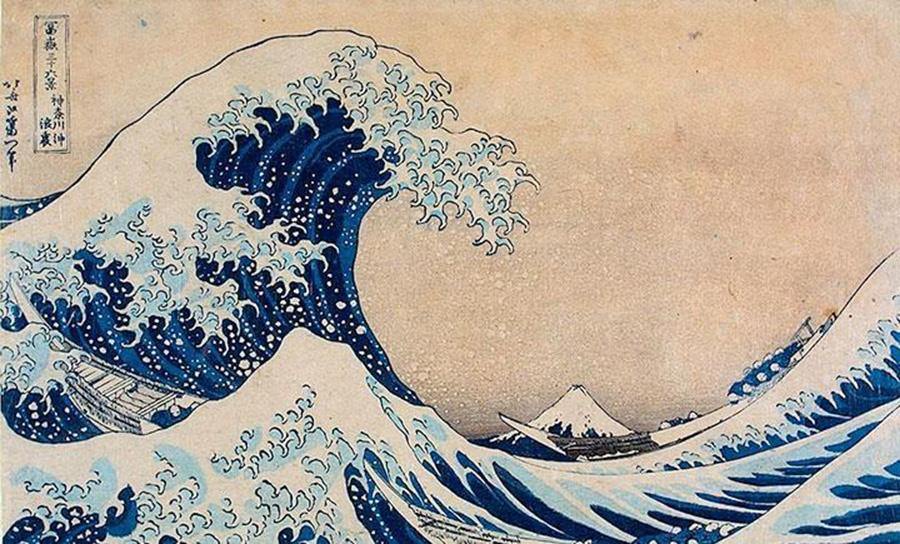

Animism in Japan

Francesco BaldessariScience is not, as many believe, accumulated knowledge but, like animism, a method of analysis. It can be summed up as “Always verify your statements against reality, and pay attention to the results of your verification.

Draw your conclusions and repeat the process”. Verification is paramount. Whatever cannot be somehow verified is irrelevant. Historiography, psychology, sociology and other disciplines partly based on subjective experience pose problems of verification, but there are ways to contain the problem through tools like statistics and polls.

The rise of of science occurred in Europe because the way we interpreted reality had already changed and we were ready to accept the results of the scientific method. Without that terrain, it would not have even been born. That terrain in Japan is largely missing.

Faith and verification are unquestionably incompatible, and science is religion’s natural enemy. This new way of looking at things, so manifestly successful that no religious authority can simply ignore it, is however neither obvious nor universal, and in fact most cultures do not recognize reason, science’s only indispensable tool, as the litmus test of reality. The Japanese consider it even negative in some cases.

But its impact on Europe and the USA has been immense, and it only takes a bit of experiencing animism to realize how big the change has been. Our understanding of reality is mechanistic and analysis-driven, and animism in Europe present but as no more than an undercurrent. Between science and animism, science wins by default. In Japan the scientific method is a module, one of the many. Useful, but not always.

Together with science, I believe the universe to be a machine obeying immutable laws that admit no exception. I also separate sharply biological events from the rest and believe objects are by definition either passive receptors of our actions—as when we demolish a house—or active in ways that are at least in principle fully predictable— as when an earthquake demolishes our house. But I deny the possibility that a non-biological entity may have attributes such as will or personality. Such entities are not, like us, free for example to use mechanical laws to their advantage, and can only passively obey them.

All these ideas are subject to continuous revisions and verifications, and adjustments to the borderline between living and not living, self-aware and not, are continuously being made. A fundamental shift from present positions is however not on the horizon.

An animist’s views are almost the opposite of mine. While scientific verification takes place against reality, animistic verification goes in the opposite direction. If a natural phenomenon can be described in anthropomorphic terms, then the description is believed to be correct even in the presence of equally valid alternatives. The explanation to the event in question has been found. Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget has called this mode of analysis “self-centered thinking” because observers use themselves as the yardstick of everything.

The cause of natural events is often found by animists in analogies, metaphors, coincidences, intuitions, dreams and other similar mechanisms of the human mind. Words, colors, sounds and other objects are attributed powers, and these powers are found and described anthropomorphically. The word long prolongs, extends. The word short reduces. The first is therefore welcome at weddings, the second forbidden because it could influence their success.

A good example of how self-centered thinking works is the yorishiro, which we have already seen. A yorishiro is any object that kami like to choose as an abode, usually an extraordinary looking thing like Mount Fuji. But since things are extraordinary when so defined by the Shinto priest, he or she is manifestly creating the yorishiro in his or her own image.

Traditionally, people covered mirrors to avoid demons coming out of them. A world was presumed to be on the other side because it looked like there was one. In Japan blood group AB is widely considered, by analogy, an index of a split personality, even among educated people. I was once asked my blood group by a psychiatrist I had been sent to because of a recurring headache. The blood of a long-necked turtle is supposed to be good for your sexual prowess because of the neck’s length and the resemblance between the turtle’s shell and the glans.

What is colloquially known as animism, believing that objects have a soul, is one of the consequences of the self-centered analysis. Human content is projected on nature so that, where we see trees, stones, wind and water, animists see living creatures, each with personality, opinions and wishes. The clean, comforting division that we have come to expect between beings and things is just not there, and not simply biological, but human qualities are attributed to inanimate objects. Every contact is seen as an interaction with signals going in both directions. Natural events are changed into messages specifically meant for oneself. Diseases assume a moral quality because they are interpreted as a punishment. Sudden wealth is not luck but a reward.

If the course of events takes an otherwise inexplicable turn, the explanation is sought among objects. Objects however do not communicate in ways that can be detected by regular human beings, so an understanding of their intentions is reached indirectly through a specialist, for example a fortune teller, a shaman or shamaness, or other such figure.

Invisible and undetectable agents, in other words spirits, are a necessary ingredient of the mix because the constitute the cause of events.

Life is therefore far from simple for someone trying to mind his or her own business, as everything talks to everything else and, in the chaos of conversations going to and fro, you are never sure that something may be talking to you and not to someone else.

Arbitrariness of events is inbuilt in the system because countless objects around you have free will and act without obeying to a moral law, for animism is incapable of producing one.

This arbitrariness is reflected in the Japanese idea of defilement, or kegare1. Unlike sin, that involves some kind of action, and therefore responsibility on your side, defilement is usually involuntary or, at the very least, undesired. Significantly, the word is written using with the Chinese character for “dirty” pronounced differently, and dirt is itself a form of kegare.

Japanese hygiene and order therefore often have an obsessive quality, and cleanliness is never sufficient. Autumn leaves are messy.

It is worth remembering that your lack of responsibility doesn’t make a difference: you will nonetheless carry a stigma, sometimes very serious. The end result is that even an exemplary conduct will not save you from problems. There is no security in probity, hence the continuous uncertainty in the life of an animist.

If you have trouble understanding the concept of defilement, think of it as a form of radioactivity. Exposure, even involuntary, will make you radioactive and a danger to yourself and others.Typical sources of kegare, besides dirt, are death and menstruations. A woman’s internal bleeding, even when manifestly not dangerous to her health, mimics a disease sufficiently to trigger a reaction.

All this, true in general of animism, applies in full to Japan. The reality of a Japanese is not western reality. In Japan magic exists because things have free will and do not have to obey the laws of physics.

While masters of technology—but mind you, technology is not science. The understanding of principles and causes is not strictly necessary to make things—the Japanese do not share our essentially Newtonian world view. Japanese were fantastic at making steel centuries before they understood through western chemistry what their Tatara smelters were in fact doing.

According to science, the behavior of things is at least in principle predictable. Things fall down, not up. In Japan this is generally (but not necessarily) true because things can act independently, essentially of their own volition. And decide to fall upwards. The world view of the Japanese is closer to that of Merlin the magician's than to ours because they do not truly believe in science.

They find science practical, but not an absolute truth, so they ditch the scientific method when they think it isn’t necessary. They do this as well with Buddhism, Confucianism and Shintō, picking out the module needed at the moment and then putting it back in its drawer. The hand that chooses the tool to use each time and withdraws it after use is always animism’s, as it is natural because it is a precursor of every other belief system in Japan.

This manipulation can be done on such a scale only because self-consistency is considered as neither necessary nor a value. This in my view is itself a result of the profound anti-rational vein present in animism. Being self-referential, animism lacks mechanisms of self-verification and correction.

But this primacy of animism is the reason understanding it is a must if we are to truly make sense of Japan.

( From Chapter Four of my next book, The Land Where Things Can Talk, to be published next year. )

Francesco Baldessari