Thought and Desire. Part 3

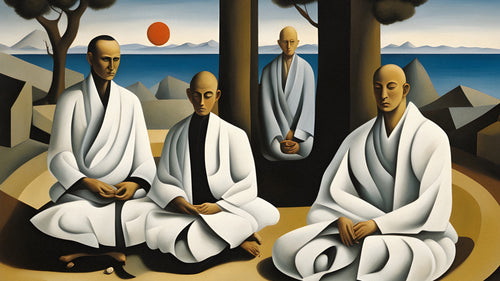

Alessandro Rusticelli4. Desire in Hinduism and Buddhism

Hinduism has always recognized the dynamic nature of desire and its poetic force, indeed it has even venerated it. From the very beginning, the mythological figure of Kamadeva, the god of desire , has occupied a prominent role in Hindu literature.

In the Atharva Veda, for example, Kama is mentioned as the most powerful of the gods and an entire hymn is dedicated to him.

In the Rig Veda it is even described as a force capable of arousing in Brahma the impulse to create the world.

Initially, desire is seen in mainly cosmological terms: it is the cause of the differentiation of phenomena from the One and therefore of the birth of reality as we perceive it. As David Webster points out, it is depicted as a force that acts on the mind of man almost from the outside, to indicate how it goes beyond any rational possibility of control. Desire, that is, acts despite the person, exercising its creative power through him.

With the maturation of Indian philosophical thought and the advent of the Upanishads, the analysis of desire becomes more and more psychological. Kama is not only a constituent of the cosmos, but also part of the experience of every individual. This internal force is seen as the motive of every physical and mental action (thinking) and as such is implicated in the karmic process and in the perpetuation of the cycle of samsara.

Gradually, then, the reflection of Hindu philosophers shifts from the generative power of desire to its regulation. The gods can create with the instrument of desire, but human beings who try to exercise this power for their own ends must be cautious because it can overwhelm them. The idea begins to mature that desire is something to be removed, transcended or disciplined because it is dangerous for the spiritual life of man and his liberation.

The analysis of the relationship between desire and suffering will be further explored by Buddhism. The passage from desire to unhappiness is a process very well described by the Buddha. According to him, the human being lives perpetually in a state of dissatisfaction: if we look closely, it is a suffering that is not inevitable and does not come from outside. It originates within us, from the fact that we think we can find lasting happiness in what is instead transitory and subject to change.

Desire in itself is not a negative force, but it becomes a source of unhappiness when it is misplaced, that is, when it is directed toward something we cannot control or that is destined to change and vanish. Our desires are constantly deceived by the transience of existence, and in this way their creative power dissipates, leaving only pain in its wake. Only by learning to recognize and appreciate the world in its transience can we arrive at a life capable of true joy and creativity. As our Seneca said: nothing makes man happy, unless his mind is reconciled with the possibility of loss.

Some Buddhist reflections on desire may bring to mind the psychoanalytic idea of sublimation. This is a psychological concept introduced by Freud, and later developed by other theorists, including the aforementioned Lacan. It refers to the process by which unconscious desires are transformed into socially acceptable, creative, or productive behaviors.

In essence, sublimation channels psychic energies into constructive, socially relevant behaviors.

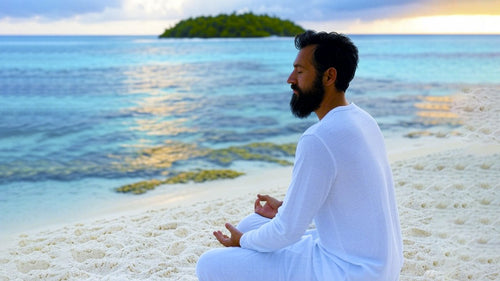

Although sublimation is not explicitly mentioned in Buddhism, the idea of a process of transformation and transmutation of mental energies through the practice of meditation and the cultivation of qualities such as equanimity and compassion is present.

In a certain sense, this emotional alchemy allows the individual to use his or her resources in ways that contribute to the growth and well-being of himself or herself and others, broadening his or her perspective beyond the narrow confines of the Ego.