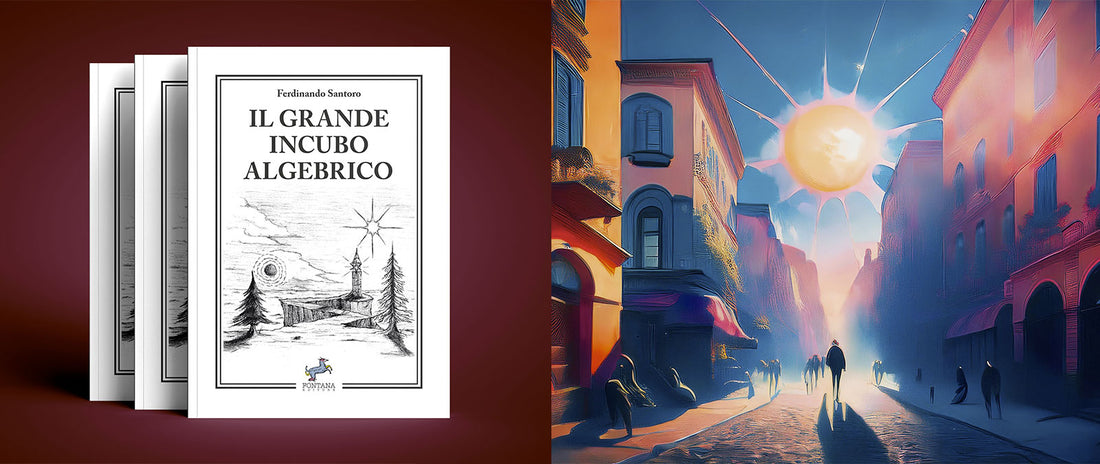

The Great Algebraic Nightmare, We Interview Ferdinando Santoro

Rocco FontanaHere is the interview with our author Ferdinando Santoro, author of "The great algebraic nightmare", an interesting conversation about the essence and themes of his book. Santoro is a young philosopher (and musician) who struck me for his bold approach in his writing and for the metaphor he uses to denounce the new paradigms of society that have developed in recent years, especially in conjunction with the infamous pandemic, which is as apt and cutting as ever.

1. What is the origin of the metaphor of the "new sun" and the "old sun" in your book? How did the idea of contrasting the "precise and mathematical light" of the new sun with the more uncertain and soft luminosity of the old world arise?

To say that I know how any metaphor in the nightmare took shape would be a lie. However, thinking about it in hindsight, I have come to understand this: I have slept for most of my life in a room that is lit by the night light of a lighthouse. Certainly this must have influenced me without my realizing it. But to answer more directly, I write in a rush, starting from sudden suggestions. I remember having the idea for the first lines of the book when I had not yet begun my philosophy studies, and having developed everything else from there, including the ideas of the old and new sun. I believe that my unconscious worked for me in finding a metaphor that would be suitable to explain the strange, very strange shift in the philosophical/moral paradigm of the last few centuries. I was struck by lightning, when I understood that in our times we must unsheathe the sword to demonstrate that two plus two equals four (semi-quoting Chesterton). The metaphor then strengthened over the course of the book because I found what came out of writing without thinking too much effective.

2. What role does "nostalgia" for the indefinite world play in your reflections? The men of the past in your book seem to feel a sense of loss for ancient uncertainties. Do you think that even today we experience a similar nostalgia in the face of extreme rationalization?

Of course we live it, and what's more we live it without realizing it. The age of technology announced by Heidegger is overwhelming for the entire emotional and intimate sphere of man, forced to live confronted in a public manner only with materiality, while his intimate and spiritual questions are left to his personal and isolated reflection. I find it boring to live in an age where there is an explanation for everything that is technical, and practically none for what concerns intimate research. There are no organized philosophical and spiritual teachings, or at least there is no serious institutionalized intention to provide for these needs of man. Of course, sometimes I wonder if this is possible or if it is not utopian, but that is another matter...

3. What do the "numbers and geometric shapes" that dominate the new world represent? To what extent do you see this geometric precision as a threat to the freedom of the indefinite and the mysterious in human life?

The threat is the same as trying to focus the sun's rays with a magnifying glass: the risk is getting burned. The frantic search for an explanation for everything has replaced the provident god of a few centuries ago. Today "science" has an answer for everything and doubt, which absurdly is the first genuine step of the scientific method, is practically illicit. And this is the real theme of the nightmare: the desire for certainties. Even if they are false or absurd. Certainties as a shield from the unknown, from the evolutionary process and ultimately from death. The important thing is that modern man, slave of the new sun, does not run the risk of mystery.

4. How do you interpret the "longing for order" and the need to control and delimit the world? Your book describes this need as a sort of "leash". Do you think that modern man has become a prisoner of this longing for control?

Yes, absolutely. Modern man is the one who feels safe if the industry writes the number of calories on the back of its packaged product. He can even ignore the ingredients, because he already has a good feeling of being in control... thanks to science, of course.

The brave man accepts his finite nature and rejects the reductionist approach, I believe. And only in this way can he truly move from the nervous emotional state of fear to a more noble one, of someone who knows that existence cannot be resolved into numbers.

5. What is the "moral" that unites the compass-men of the new world? The "new world" seems to have its own ethics, based on equality and pragmatism. What risks do you see in this homogenizing vision of progress?

I think this question is inspired by the opening episode of the book, when the old sun is buried. I would like to point out that not all the metaphors of the nightmare are deeply thought out, and not all the dialogues are measured to the millimeter (to stay on the subject of geometric precision). This is to say that the believer who reproaches the morality of equality to the man of the new sun, does so without thinking too much. In fact, this dialogue did not mean to say that the morality of the new world is based on a wrong equality or something similar: in this case there is no need to read too much between the lines. I am perfectly aware that this is a book that lends itself to all sorts of misunderstandings, but this is the only way I managed to write it.

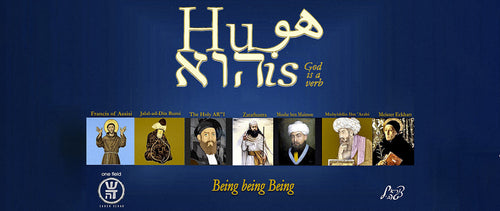

6. Who are the men-compass today and the men of the past, in your opinion? The description of the book seems to allude to two different mentalities in today's world. To whom do you think these roles can be attributed today?

To avoid any misunderstanding, I would like to say that the compass, the square, etc., are not references to Freemasonry (I say this because various people have pointed out to me the similarity with Masonic symbolism, which I knew nothing about when I was writing the book).

The metaphor is a reference, in fact, to two human attitudes. One of extreme control, aimed at eliminating all uncertainty, even with false certainties, at the cost of preserving one's illusion of control and thinking that one can thus dominate the complex nature in which we find ourselves existing.

The men of the past, I called them that for literary reasons in the book, but they are a humanity exponent of an attitude that, in reality, coexists with the men-compass of every era. That is, the acceptance of doubt, of uncertainty and of ultimately knowing nothing about physics or metaphysics. I consider this a more humble and genuine way of seeking, of philosophizing. Seeking, doing science, without the illusion of being able to grasp anything. If we find ourselves within creation, how could we ever understand it? It is as absurd to think of being able to understand creation from the inside as it is absurd to think that the figure in a painting can understand the painting.

7. What value do you attribute to the "rebellion" that ignites in the young man? This character decides to "steal" the remains of the old world as a sign of resistance. What message do you intend to convey to readers with this image?

The message is clear: not resigning yourself to a world that is taking an unjust turn. Stealing the remains of the old sun means keeping alive the hope of a more authentic way of interpreting reality, even if the lighthouse keeper will then push the faithful to free themselves from any interpretation of the world imposed from above... "New sun, old sun, what difference does it make?"

Another intention hidden by the metaphor is to go against the absurd logic that every novelty is good and better than what came before. The awake man recognizes the folly of the age that is about to dawn and runs for cover, swearing fidelity to a better past. Not out of nostalgia, but out of philosophical objectivity.