The Glass of Antimony: Operative and Alchemical Considerations

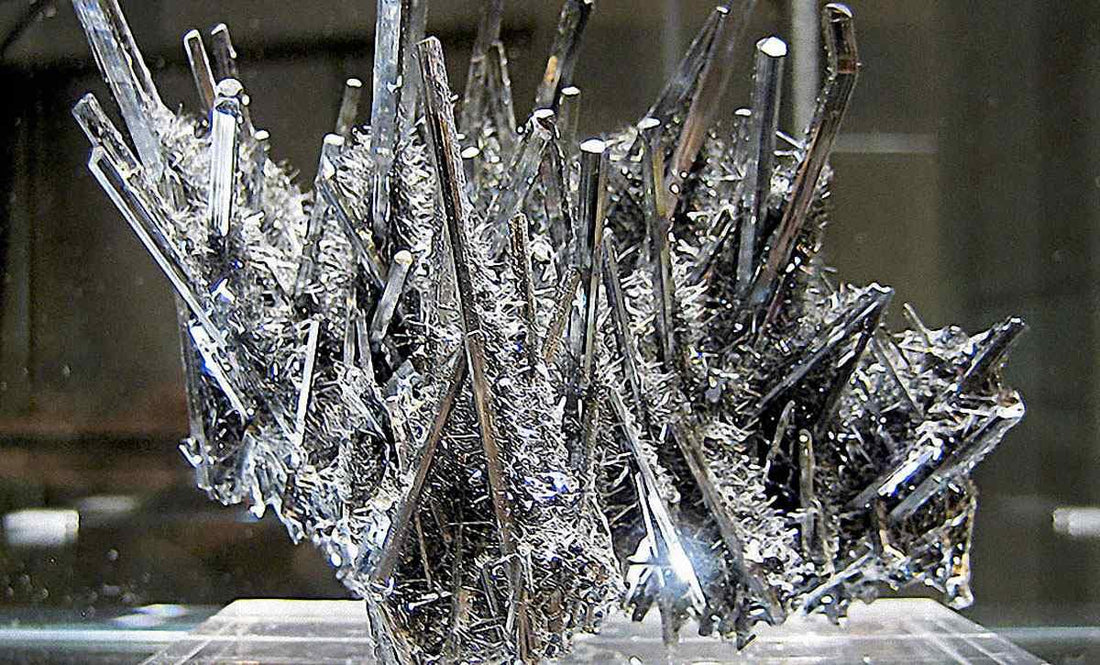

James CollinsBy James Collins. While antimony was already well established as a building material used for making glass in many European churches[1], one of the first literary sources of it being used as a medicine was in Basil Valentine's "Triumphant Chariot of Antimony"[2].

Despite being ridiculed by the medical community for using a virulent poison as a medicine, he seemed to have much success in its medicinal applications, from treating wounds to curing breast cancer, syphilis and leprosy.

In his book, Basil Valentine gives over three dozen different "recipes", all using antimony or its ore, the mineral stibnite. Many combine this poison with other ingredients such as potassium nitrate, acetic acid, potassium carbonate, and many others, all with the aim of extracting the "medicinal" virtues from the mineral and leaving behind the "poison". Indeed, Dr. Lawrence Principe, followed Valentine's recipe for making the "Oil of Antimony", as described in his article from Ambix[3]. After chemically analyzing the final product, it was found that no antimony or antimony salt was present.

In reading Valentine's book, it will be noticed that more than a few of the "recipes" given start as a first process with making the glass of antimony. He indicates that the yellow glass is the best, but in my own experience, while the yellow glass can be cumbersome to obtain, the red glass is a close second in terms of how well "tinctures" and "oils" can be extracted from it. Dr. Principe was able to make an oil from the yellow glass, and I was able to make the same using red glass, so the two seem to be somewhat interchangeable. Valentine indicates that indeed "all colours can be obtained from antimony;" I myself have obtained red, yellow, black and orange glass, and I would imagine that with varying amounts of heat and various ingredients, other colours such as blue and green can be obtained. Even a clear glass of antimony can be made[4].

In my own work with antimony, my first project was with making the glass. But I was not doing the work from a chemical perspective - rather it was from a more alchemical one. I wasn't interested in the chemical properties and reactions of the substances being used, nor was I attempting to verify the veracity of Valentine's work. I was rather attempting to discover what personal, perhaps even spiritual benefits I could obtain from doing this work. In alchemy, a primary precept is "As Above, so Below." In other words, what is going on physically in the work being performed and with the materials being purified and refined has a psychological, perhaps even spiritual counterpart in the alchemist him- or herself. One only has to look at the huge amount of literature by Carl Jung to verify the truth of this. I was attempting to see how all this applies to this particular work, which will be described below.

Before going further, I should point out that if the reader wishes to replicate this work, using protective equipment cannot be overstated. Use welding gloves, face and eye protection, and mask at the very least. Do not use any equipment without having proper training first.

At first I was attempting to create the yellow glass, since Valentine lauds it so much; but instead what I got was the red glass. Perhaps this was from a lack of experience and that my technique wasn't very refined at the outset. I started by taking the ore of antimony, stibnite, which I obtained in crystal form from China. This particular ore had a lot of impurities in it, including calcite and quartz (which in the end benefited me quite a lot, as will be explained shortly). This was powdered in a wrought iron mortar and pestle until it was very fine, almost like flour. Surprisingly, this was a very meditative procedure, as I became enthralled by the motions. It was strange, by I was transfixed, despite my neighbours seeing me outside grinding away wearing gloves and a mask. When I had a practical amount of the very fine powdered stibnite, I moved on to the second part of the procedure, which was to "roast" the stibnite. Valentine did this over a fire, but being constrained by local law I chose instead to use a portable, 1000W cooking range. By sprinkling the powder in a very thin layer (approximately 2mm deep) on a cast iron pan, I found the roasting to proceed very easily. It took a lot of effort, yes, since the stibnite had to be stirred every ten minutes or so, and in total a single roasting took about twelve hours, but within a week I had about half a pound (200g) of roasted stibnite. During the beginning of each round of roasting, once the stibnite reach the lowest temperature possible from the cooking range (~100C), a very strong smell of sulfur was emitted. This is due to the sulfur in the stibnite being exchanged with oxygen from the air, hence the need for constant stirring, as it is the exposure to not only heat but also air that makes the "roasting" possible. Needless to say, I held my breath each time I stirred the matter in the pan. (If the reader is wondering for the safety of my neighbours, the setup was well away from them in the corner of my backyard, where the wind would carry it away.) Every half hour, the temperature of the pan was marginally increased, such that by the end of five or six hours, the range was at its maximum temperature (400C). As the temperature of the pan was increased, more and more sulfur was replaced with oxygen in the matter, which made it appear lighter in colour. What started as a dull grey progressively went to a burnt red colour, which then lightened to a beige with a very slight hint of red. Looking back on my work, I realized that by the end there was still a very tiny amount of sulfur in the matter (which gave it the slight red tinge), while the majority of it was a very light beige colour (antimony trioxide). I could have roasted it further, making it a complete, homogeneous light beige with no hint of red, but in my impatience (yes, I was an impatient, rookie alchemist back then) I decided to go on to the next step.

This was the more... influential part of this work in terms of its impact on me. I used a jeweler's furnace with a graphite crucible: First, the crucible itself was heated to 900C, then the powdered and roasted stibnite was put into the crucible spoonful by spoonful. (Again, for peace of mind, only use forges if you have been properly trained and have proper protective equipment. The fumes emitted in this experiment are extremely poisonous.) The stibnite powder melted fairly quickly and fumed quite a bit. Needless to say, I wore protective equipment and stayed well clear of the fumes. Luckily, I did this work during a weekday when the neighbours were at work and wouldn't get concerned with the sheer amount of smoke being produced by this work.

At this point, Valentine says checks should be made on this molten stibnite using an iron nail, by dunking it into the molten matter in and out very quickly, so that a small amount gets attached to the nail. This was done once every few minutes as soon as the stibnite melted. The first few had only a dark grey glean to it, but within about fifteen minutes the molten stibnite turned into a bright red, as seen in the picture. This was then immediately poured onto a heated copper plate.

Many who have attempted this work have failed miserably, thinking their error was perhaps they hadn't heated their matter hot enough. I have heard of some operators heating their stibnite to over 1600C, even up to a few hours, just in case they hadn't given the glass enough time to form, only to meet with failure yet again. Yet, the solution to this problem is much, much simpler. Most of the stibnite alchemists get is from China. Dr. Principe, in the same article mentioned earlier, indicates that this particular stibnite contains little to no silica. However, it is the presence of silica that allows for the formation of the glass of antimony. It acts as a sort of catalyst, or matrix, on which the glass forms. Therefore, when no silica is present, it can be added to a 2% weight. I have used this trick myself with much success, using clear quartz crystal as my source of silica, and have obtained yellow glass of antimony.

It is the act of creating something beautiful from something so dross that in this case has a profound psychological effect on me. While stibnite crystals are beautiful in themselves, this idea of purification is more profound when stibnite clumps are used as a starting material. At first glance, one wouldn't think that something so beautiful can come from something so dross. This idea is carried into the psychological realm, not just in therapy, but also in art. But more importantly it applies to personal purification and growth, starting from base emotions, impure thoughts, habits and tendencies, to the "complete" or "fully developed" or "self realized, individuated self". One only has to look at religions like Buddhism to see this act of self development constantly at play. When I was making the glass of antimony, I couldn't help but think of this concept. No matter what the starting material, whether it be a plant or mineral in the alchemical laboratory or the alchemist himself, this concept of purification can always be applied to extract the more pure parts while leaving behind the impure.

Did this process have a direct benefit for me? I would say yes, most definitely. Some might say that this is merely the placebo effect, and that the procedure didn't really have any effect on me. In reply I would say that this doesn't mean we should discount this effect so quickly - the power of the mind can be quite profound. I won't deny that a not-insignificant amount of the psychological effects obtained from alchemical work has its source in the mind itself, but a great majority of other alchemical products do have a direct effect, not only on the physical body but also on the mind, which can be used to further one's progress on their Path of Purification. One may not see these effects immediately - in fact, they most likely won't. It is the accumulation of experiences in both the lab and in personal meditation that the alchemist realizes that the alchemical journey is a long one, taking years to unfold.

Article published on Nitrogen 1

1. Fulcanelli, "Mystery of the Cathedrals"

2. Published in 1678

3. Principe, Lawrence. "'Chemical Translation' and the role of impurities in alchemy: Examples from Basil Valentine's Triumph Wagen." Ambix, Vol. 34, Part 1, March 1987.

4. Valentine, Basil. "Triumphant Chariot of Antimony." 1678