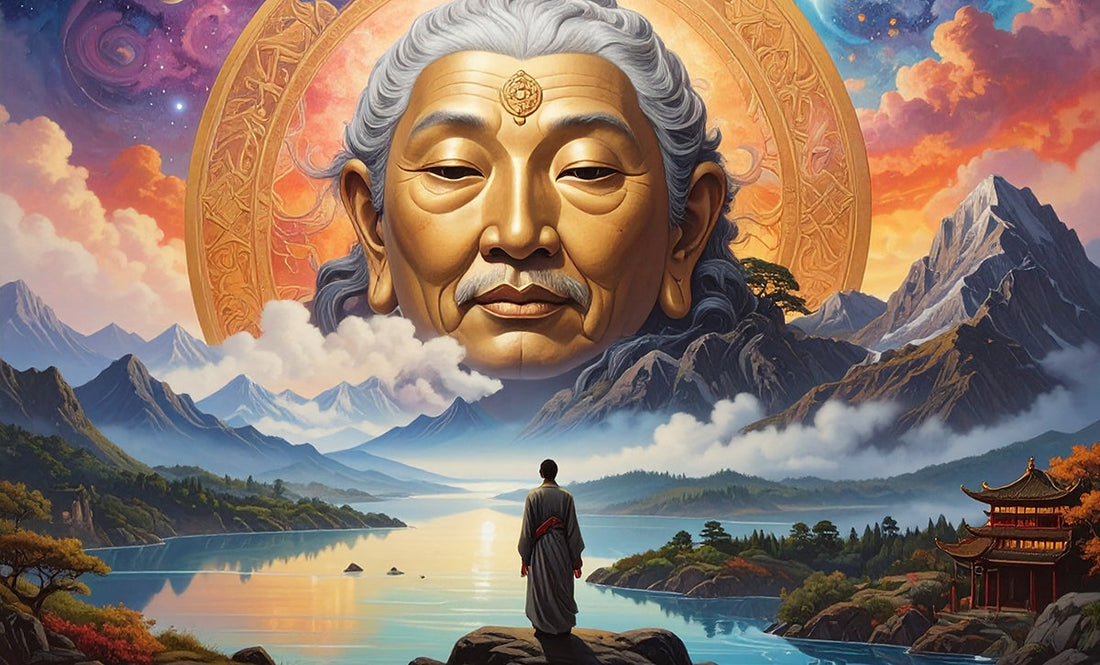

The Tao and the Art of Letting Be

Alessandro RusticelliUnderstanding Taoism isn't easy, especially for those who have never lived in China or experienced its ancient culture. But perhaps it's precisely this remoteness that is so fascinating, driving many to seek to penetrate its mystery...

Taoism is concerned with human well-being; this is its central point, unfortunately often misunderstood by intellectuals. The message is that to be physically and mentally well (the two concepts are not separate) one must be in tune with the natural rhythm of life, with the very flow of existence. In the golden age of Taoism, the current concept of mind, nor psychology, did not yet exist; when we read the classics of this tradition from our modern perspective, they seem to describe something abstract, a metaphysical reality hidden behind the ordinary, but this is not the case.

If we could meet Laozi and tell him that we interpret the Tao as a remote and transcendent law, he would hit us hard! The Tao is, in fact, the reality we experience right here and now, constantly changing; to live well—virtuously, as the Chinese sages would say—we simply need to rediscover how to connect with it. This is not easy for us Westerners who, driven by the need for security, compulsively attempt to organize the world into clear-cut and distinct categories.

For Taoism, thinking about the absolute is absurd: it's a pointless intellectual exercise. Rather, we must embody and feel with every fiber of our being the existence of which we are a part, transcending our rigid vision of the world and ourselves.

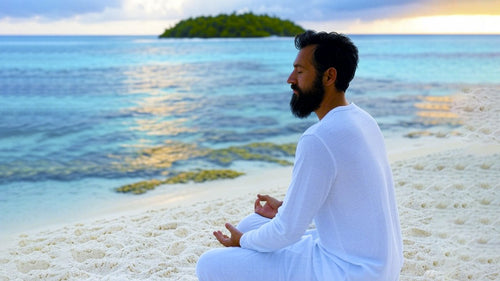

A quiet Taoist temple in northeastern Taiwan

The concept that perhaps best sums up all this is Wu Wei (無為). Literally meaning "not acting," this translation risks being misleading. Wu Wei does not invite us to inactivity, nor to passive torpor, but rather to a way of being in the world that flows as naturally as water finding its way between rocks. It is the art of acting without forcing, of letting things happen without imposing our will on what is living and continually transforming. The Tao Te Ching, the founding text of this "philosophy," expresses the principle with these words: "The wise man does not act, yet nothing remains undone."

Here, wisdom lies not in redoubling one's efforts, in chasing results and conquests, but in freeing oneself from the compulsion to control and shape everything according to the ego's desires. The path (Tao) unfolds by itself, and man's task is to learn to follow its rhythm, rather than fight it.

What's surprising is that an echo of this insight also resonates in the heart of Western philosophy. Martin Heidegger, one of the most enigmatic and controversial thinkers of the twentieth century, reflected extensively on how we all relate to being. He saw modernity as a constant temptation to dominate: the world reduced to an object to be calculated, organized, and consumed.

This mania for possession leaves no room for a genuine encounter with what is. In his later writings, such as "Abandonment," the philosopher from Meßkirch proposes a different attitude, one closely reminiscent of Chinese wisdom. He speaks of an inner availability that does not impose, but welcomes; an openness that does not force, but allows.

Like the Tao, it suggests going with the flow without resistance. Heidegger invites us to pause in the openness of being, without reducing it to a mere instrument of our will. Two worlds, two languages, two distant eras: yet the gesture is the same: that of letting go of obsessive control to inhabit life with greater authenticity.

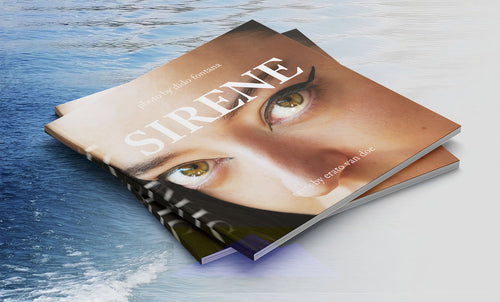

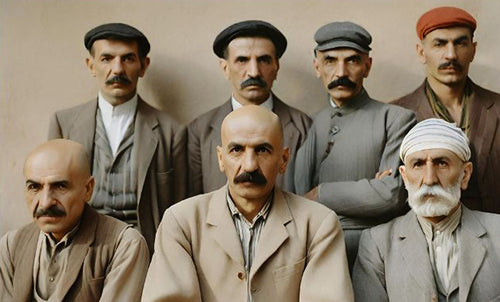

Meditation Master Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche During Dzogchen Practice

Isn't this the primary purpose of meditation? Although neither the Taoists nor Heidegger promoted this practice, it is perhaps where the profound meaning of Wu Wei is most evident. It's not about forcing the mind to be quiet, nor constraining it within pre-established patterns; on the contrary, the practitioner learns to allow thoughts to arise and vanish like clouds in an open sky. There is no struggle, no repression: only a silent presence, allowing things to happen without identifying with them.

“In the Middle Way, ordinary mind is the simplest term. It's the most immediate way to describe how our nature really is. It means that nothing needs to be accepted or rejected; it's already perfect as it is. Don't project yourself outward, don't retreat inward... there's no need to pursue a forced state of calm. We must free ourselves from thoughts of the three tenses [past, future, and ruminations on the present]. There's nothing easier than this. It's like pointing to space. That's it. That's the moment when no doing is required. The essence of the mind is originally empty and rootless. Knowing this is enough in itself.”

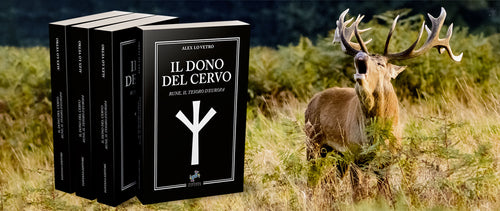

From this disposition flows a tranquility that is not artificial. It is the serenity of the river that, by not resisting obstacles, circumvents them; the trust of the mind that rediscovers its original harmony, what Morihei Ueshiba—the Japanese educator and founder of Aikido—called "aiki." The reference to this discipline is not accidental: I practiced Aikido for years under the guidance of a Chinese master, who, in addition to teaching me the technique, tried—despite immense linguistic difficulties—to instill in me a way of life, namely that of Taoism. My journey was troubled and full of doubts, but in the end I learned that if you want to achieve something, you have to stop clenching your fist: it is much wiser to gently open your hand. If you want to arrive, you have to stop and learn to grasp the direction of the energy that guides our lives. But that's another story, one we may address elsewhere.

The author and Master Jian during an Aikido demonstration in Taipei. The technique not only embodies the Taoist principles of natural and effortless response, but also visually evokes the shape of the Tao symbol.

Returning to the topic of meditation practice, a Tibetan master—Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche—used to say that when we remain still, there is a total letting go. When this happens, we discover the sensation of being completely awake, a quality of mind that is not fabricated, but entirely innate. According to Tibetan Buddhism, this is the highest form of meditation, where meditation is no longer an act but a spontaneous posture of the mind.

Many have spoken of it, from Tich Nath Han to Krishnamurti, including the Zen masters of the Japanese tradition. For all, this spontaneity is the highest form of spirituality. But be careful not to misunderstand: in Taoism and Zen, naturalness (ziran ⾃然) and inaction do not mean passively resigning oneself to everything that happens, including evil. Rather, it is about acting without forcing, without going against the natural rhythm of things. It is a way of acting that does not arise from indifference, but from harmony with reality. What we call "evil" is instead the result of an imbalance, and imbalance always brings suffering. Inaction means contributing to the restoration of harmony, not perpetuating disharmony!

1 comment

Bel post, interessante ed esposto con chiarezza.

armando piovesan VI dan Aikido Hombu dojo Tokio